Ticking like Hans Zimmers, a company technique

- Audio

- 6 March 2025

Mathilde Pottier

Designer & Founder

It begins with a sound. Not a melody, not a note – just a ticking. A minimal, repetitive gesture measures time, marks it, and divides it. For centuries, people have listened to this sound to organise their lives. In houses, in towers, on wrists, the ticking has always been there. But what happens when this signal – originally meant to reassure – becomes something else entirely? In the hands of a composer like Hans Zimmer, it is no longer just the background noise of time passing. It becomes a material, a tool, a method. It is stretched, compressed, distorted, and repeated. Likewise, it creates tension, urgency, and sometimes discomfort. From the mechanical rhythm of old clocks to the controlled chaos of Dunkirk, ticking evolves. It is no longer passive. It shapes perception. Whether in music, cinema or watchmaking, ticking reflects how we experience time – not as a neutral flow, but as a presence that we can hear.

The Hans Zimmer's ticks tocks compositions

The Hans Zimmer’s story

In the late 1970s, a young German musician was exploring the possibilities of machines in a small London studio. His name was Hans Zimmer, born in Frankfurt in 1957, and what interested him was not so much melody as the texture of sound. He began by tinkering with synthesizers, mixing electronic sounds with traditional instruments. In 1988, with the Rain Man soundtrack, he established his signature sound: electronic layers mixed with classical orchestrations, creating an unstable, sometimes minimal soundscape. From his early successes, he developed a working method centred on the construction of blocks of sound. He collects raw materials – springs, breaths, engines – and assembles them in repetitive sequences designed to create a constant tension. The Lion King, Gladiator and his collaboration with Christopher Nolan have consolidated this style. Zimmer thinks of music in terms of editing: duration, rhythm, saturation, and editing.

The Dunkirk’s ticks and tocks

In 2017, Hans Zimmer was working on Dunkirk. An idea soon emerged: to integrate the sound of a clock into the structure of the music. He asked Christopher Nolan to record the ticking of his watch and then reworked it. The sound is compressed, shortened and made drier. It becomes a rhythmic element, but above all, a psychological one. The ticking doesn’t mark time: it speeds it up, ruins it, makes it threatening. Zimmer integrates it into the soundtrack as a central motif, combining it with continuous layers and muted textures to create a tension that never lets up. This ticking is then gradually and imperceptibly accelerated until it creates an almost physical sense of urgency. It no longer follows the action: it conditions it. The viewer is not watching a scene under pressure but experiencing it. For Zimmer, time is no longer a frame. It is a dramatic tool in its own right.

The ticks and tocks companions

One tick is not enough. Repeated in the same way, it quickly wears out. Hans Zimmer knows this, which is why he never uses it in isolation. To keep the tension up without tiring, he combines it with other sound textures to create dynamic contrasts. He combines it with heavy, often muffled percussion that alternates with the dry, regular rhythm of the ticktock. The result is an unstable beat, like an irregular heartbeat. Added to this are strings under tension, mainly violins and violas, which slowly build in intensity, bringing a more organic emotional charge. At times, he also manipulates the sound of the ticking clock itself: reverberations, echoes, filtering, so that it sometimes seems distant, oppressive. Nothing is left to chance. Each sound is calibrated to fit into a moving whole. The ticking is no longer a mechanical noise; it becomes a living motif, linked to the inner state of the viewer.

People relationship with the time's sound

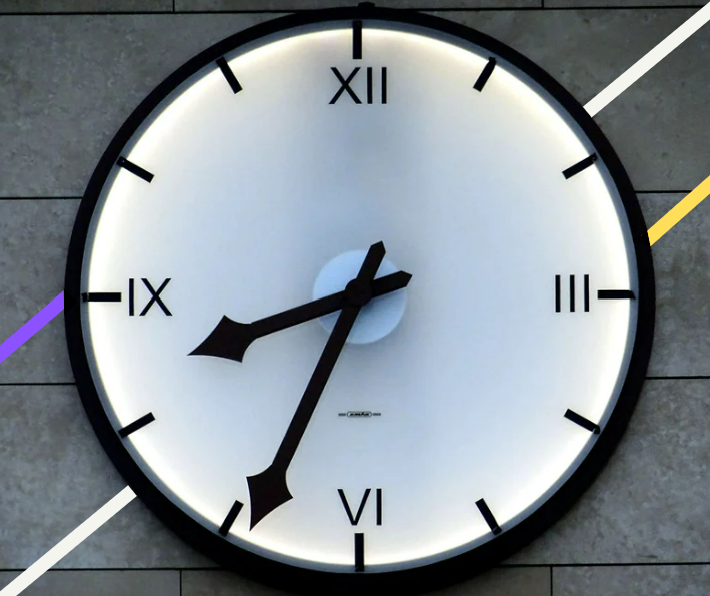

A history of mechanics

Before electronics, we listened to time. For centuries, mankind measured the hours using simple but rigorous mechanisms, all based on the same principle: a regular movement, a repetitive sound. Ticking dates back to the 13th century, with the first European mechanical clocks. The heart of the device is based on the escapement and the balance wheel, the alternation of which creates an audible rhythm intended to mark time as much as to feel it. In the 19th century, Maelzel’s metronome applied this regularity to music, providing musicians with a reliable guide to tempo. Even today, some mechanical clocks, kitchen timers and digital applications still use this sound marker, synonymous with constancy. Ticking has become a cultural code associated with precision, control and the structured passage of time. In homes and on church steeples, it marks not only the hours but also the collective imagination.

Andrik Langfield

An invitation to self-consciousness

Before electronics, we listened to time. For centuries, mankind measured the hours using simple but rigorous mechanisms, all based on the same principle: a regular movement, a repetitive sound. Ticking dates back to the 13th century, with the first European mechanical clocks. The heart of the device is based on the escapement and the balance wheel, the alternation of which creates an audible rhythm intended to mark time as much as to feel it. In the 19th century, Maelzel’s metronome applied this regularity to music, providing musicians with a reliable guide to tempo. Even today, some mechanical clocks, kitchen timers and digital applications still use this sound marker, synonymous with constancy. Ticking has become a cultural code associated with precision, control and the structured passage of time. In homes and on church steeples, it marks not only the hours but also the collective imagination.

The ticks tocks as a stressful source

In a quiet environment, the ticking attracts rather than guides the ear. This mechanical, regular sound attracts attention without releasing it. In a bedroom, waiting room or library, it ends up being a distraction. It interferes with thoughts, disturbs concentration and creates latent tension. Some people are particularly sensitive to it. For them, the phenomenon has a name: misophonia, an intolerance to repetitive sounds. Cinema has made this sound motif a common tool for creating tension, especially in suspense or countdown scenes. But the effect is not limited to fiction. During an exam, an interview, or a moment of pressure, a simple clock is enough to create real unease. The regular sound no longer helps to structure time; it becomes a distraction, even an obstacle. Always present, it imposes a rhythm that we do not choose.

Jaeger-Lecoultre and the ticks tocks strategy

Jaeger-Lecoultre

A Franco-Swiss history of time

In 1833, in the heart of the Vallée de Joux, Antoine LeCoultre founded a workshop dedicated to precision mechanics. His instruments soon became renowned for their sophistication. In 1844, he perfected the Millionometer, capable of measuring to the nearest micron, a first in the history of watchmaking. At a time when precision was still based on intuition, this tool changed the game. The company established itself as a manufacturer of complex, durable watchmaking calibres. In 1937, it merged with the French company Jaeger to form Jaeger-LeCoultre. This alliance gave rise to some iconic timepieces: the Reverso, designed to withstand shocks, the Master Control, a guarantee of precision, and the Atmos, a watch that works based on temperature changes. Today, the brand remains faithful to these aspirations: each tick is the expression of a balance between invention, tradition and absolute mastery of time.

The ticks tocks system

In a mechanical watch, the ticking is not a matter of decoration. It is the result of a precise system: the escapement, which regulates the energy transmitted to the hands. At Jaeger-LeCoultre, this mechanism is meticulously designed and is at the heart of each in-house calibre. Unlike quartz watches, where the second hand jumps forward, a mechanical watch produces a faster, smoother, continuous ticking that is perceptible in a calm environment. Some emblematic models, such as the Atmos, operate without manual winding, taking advantage of temperature variations. Their internal rhythm remains stable, almost imperceptible, but perfectly timed. This regular sound is not just a sign of operation: it reflects a demand for precision. Timepieces such as the Master Grande Tradition Tourbillon take this logic to the extreme, integrating complex systems to stabilise each beat, limit deviations and guarantee reliable and constant timekeeping.

The ticks tocks identity

At Jaeger-LeCoultre, the ticking is not concealed: it is enhanced. Contrary to other brands that try to eliminate the noise of movement in favour of fluid silence, the Swiss brand makes the mechanical sound a defining element of its identity. In several of its advertising videos, the ticking is integrated into the soundtrack, often highlighted in the first few seconds. This choice is not insignificant: it underlines the physical presence of the mechanism, the rigour of the assembly and the object’s mastery of time. The Atmos, the brand’s emblematic watch, embodies this philosophy. Its discreet but constant rhythm has become an instantly recognisable sound signature associated with the Swiss watchmaking tradition. In certain demonstrations or advertisements, the beating of the calibre can be heard. Far from being a mere detail, this sound has become a sign of precision, an almost audible proof of the brand’s mechanical standards.

The all-around ticks and tocks

A ticking sound is never just a ticking sound. It can carry weight, structure, and even emotion. In Zimmer’s compositions, it becomes a framework for suspense, a psychological anchor, a trigger for physical tension. In watchmaking, and particularly at Jaeger-LeCoultre, it is a sign of heritage and precision – a sound chosen, shaped and celebrated. Whether it creates stress or concentration, tranquillity or unease, the ticktock leaves its mark. It guides the listener, reminds the viewer, marks the passage of something invisible. Its regularity forces us to notice time – to feel it, to follow it or to resist it. From the concert hall to the cinema, from the metronome to the Atmos clock, it links the past to the present. This often-overlooked sound becomes a language. And behind that language is a simple truth: how we hear time typically shapes how we live it. Tick by tick, second by second, sound becomes structure.